By Andreina Soto

[virtual_slide_box id=”7″]

Roll over the images to learn more about them!

Women performed noncombatant roles during the WWI in the U.S. and in Europe. Their presence in the war, sometimes overlooked, can be observed through a wide scope of visual culture that circulated during the years of the Great War. Photographs, postcards, and propaganda show different dimensions of the female persona during this period. They were mothers, but they were also providers; they were waiting at home, but they were also in the battlefield healing the soldiers.

The visual culture and printing media that circulated during the Great War reflects the imagery towards gender roles, shows the multifaceted character of the female representations, and women’s engagement in different activities at home and overseas. Giving the inextricable relation between war and gender, the following storytelling portrays and explains some of the female representations of women during the WWI based on propaganda, photographs, and videos I have selected from digital databases related to the Great War. These resources serve to explore in more depth the role of women in the early-twentieth century U.S., which opened a road to women’s involvement in the political and public life of the country.

Women became the “second line of defense” that secured the moral, social, economic, and political sustaining of the U.S. in ways the male soldiers and civil men could not achieve. As Susan Grayzel sustains, World War I was the first modern war that required the full participation of both combatants and noncombatants, altering the battlefield as well as the domestic and social spaces of the Homefront in Europe and the U.S. Even though the outcome of WWI did not radically changed the place of women in society, this epoch did had a great influence in different aspects of the domestic and public life that affected women and men. As well as the image of the country and the male soldiers highlighted the cohesion of a national identity, the visual representations of the war also relied and engaged female imagery. At the same time, the war opened new opportunities for education, employment, and national service for women in the country and overseas, performing duties as nurses, stenographers, factory workers, food producers, among others. The composition of different types of visual culture using female models, especially in propaganda, reflect this transition.

This is a story about female imagery – how they were envisioned during the course of the war.

Visual content

This project bases on the visual analysis of different photographs and printed media -mostly propaganda- produced and circulated during the course of the Great War. In order to compile and curate the images, I have used the following digital databases:

Printed media and photographs had an important role in the distribution of information by the turn of the twentieth century. Their use seems remarkable during the course of the Great War in which, for example, a great scope of newspapers, commercial photographs, postcards, and propaganda circulated worldwide to keep the population informed.

To construct my story about female imagery in the war, I have incorporated different types of propaganda I have found at the Library of Congress Digital Collection, a very comprehensive database to locate printed media from U.S. and overseas from the early twentieth century. I have also used printed media and photographs from the scrapbooks of Alma Clarke, Frank Steed, and the Scrapbook from the Home Front (anonymous), who offer a personal perception of the war from the angle of three different persons who, from Europe and from Home, gathered, selected, and constructed their memories into scrapbooks.

The comparative examine of these sources -propaganda and scrapbooks- allows to see collective and individual perspectives based on gender, occupation, leisure activities, social interactions, and personal values.

The Storytelling

“The Second Line of Defense” goes through a main narrative, divided in four themes. Each excerpt offers a particular view or role I have defined to understand the female imagery during the WWI: Motherland, Healers, Muses, and Providers. Each excerpt is formed by a main argument presented through a comparative analysis of different visual resources. This gives the sense of an “interactive museum,” where in each gallery the user cannot just observe the visual culture but also manipulate the images and learn through the contrast between visual and writing content.

Scroll down the page to read the storytelling. You can also hover over the images to learn more information about their visual content.

If you wish to know about the composition of the storytelling, click here. Meanwhile, enjoy the wonderful story of the female imagery during the WWI.

Motherland: Female Symbolism of National Identity

In the early-twentieth century, the battlefield was considered a place solely for the male warrior to defend his nation. Nonetheless, from a century before the image of the United States had a female face that made the call and unify the people under the same national sentiment. Her name was Columbia.

[virtual_slide_box id=”13″]

Roll over the images to learn more about them!

Once the thirteen colonies began to acquire a greater sense of national identity, the image of Columbia emerged to personify this new spirit. The references to Columbia date back from 1697, when Chief Justice Samuel Sewall of the Massachusetts Bay Colony wrote a poem suggesting that America’s Colonies should be called Columbina, a feminization of Christopher Columbus’ last name. But it was not until late-eighteenth century that Columbia acquired a more meaningful place in the way United States depicted itself as a nation in search for independence from Britannia, the female representation of the empire overseas.

[virtual_slide_box id=”14″]

Columbia appeared for the first time in a poem written by Phillis Whatley, a former slave who wrote in 1776 during the revolutionary war. Since then, the image would become a recurrent symbol that unified the country.

Columbia, as well as the national embodiment of the European countries, was inspired in Roman symbols that resembled images of mythical figures. Columbia’s physical attributes and clothes gives her the image a classic goddess. Some of the representations depict her wearing a white draped garment, but during the course of the war it is also common to see her body covered with the flag of the United States.

[virtual_slide_box id=”15″]

Beside Columbia, other pseudo-mythical representations took part in the way war propaganda animated combatants and noncombatants to participate in the war. The most popular image, one that remain until our days, is Uncle Sam, who displays a male representation.

Move the arrows at the center of the image to the left or to the right to appreciate the similarities and differences between Columbia and Uncle Sam!

Nonetheless, we can notice Uncle Sam is almost coercive to the viewer, suggesting obedience or threat if the person fails to obey the call for duty. His use to encourage enlistment in the military and working duties during the war suggests his association with the governmental institution. Meanwhile Columbia, a softer and motherly image, would embody the virtuous and protective motherland.

Throughout the propaganda from the period, it is noticed how Columbia became a more powerful symbol to enact national identity, as the voice and the face of the mother -the country- who called her sons –soldiers- and daughters –noncombatant nurses, wives, and workers- to involve in the battle, to take action.

[virtual_slide_box id=”16″][virtual_slide_box id=”17″]

The image of Columbia was used to recruit soldiers as well as to request the help of civilians to contribute with the nation by preserving food, working as volunteers, and performing other duties, such as serving for the Red Cross. Along her, other female representations named Liberty and Victory took part in the advertising that circulated during the war.

Similar to Columbia, these pseudo-goddesses also use draped garments that combined white, the colors of the U.S., and physical features of classic Roman imagery. Nonetheless, these two representations also represented other meanings. Even though they suggested patriotism, their moralizing voices called the population to engage the population in different levels. For the male population, it is common to see Victory, shoulder to shoulder, holding a sword and leading the men with bravery in the battlefield. Liberty, on the other hand, called the attention of the female and the male population in the Homefront, guiding them to produce the land, to enlist the army, to volunteer as nurses.

[virtual_slide_box id=”18″][virtual_slide_box id=”19″]

The use of these different representations highlights the power of the WWI propaganda and shows the circulation of patriotic ideas that sought to create guilt, passion, and bravery among the U.S. population. Their representations, as well as their messages, also expose how men and women played particular roles in the war, the first seeking for victory, the seconds at home, securing the nation’s freedom.

[virtual_slide_box id=”20″]

Healers: Nurses in the Battlefield

Columbia called men to join the battle, but she also addressed women to travel away from home and serve as nurses and nurses’ aides for the Red Cross.

The posters from the period show a predominant use of female representations, an embracing and motherly image that suggests the role of nurses as healers of the physical and moral state of the men.

[virtual_slide_box id=”21″]

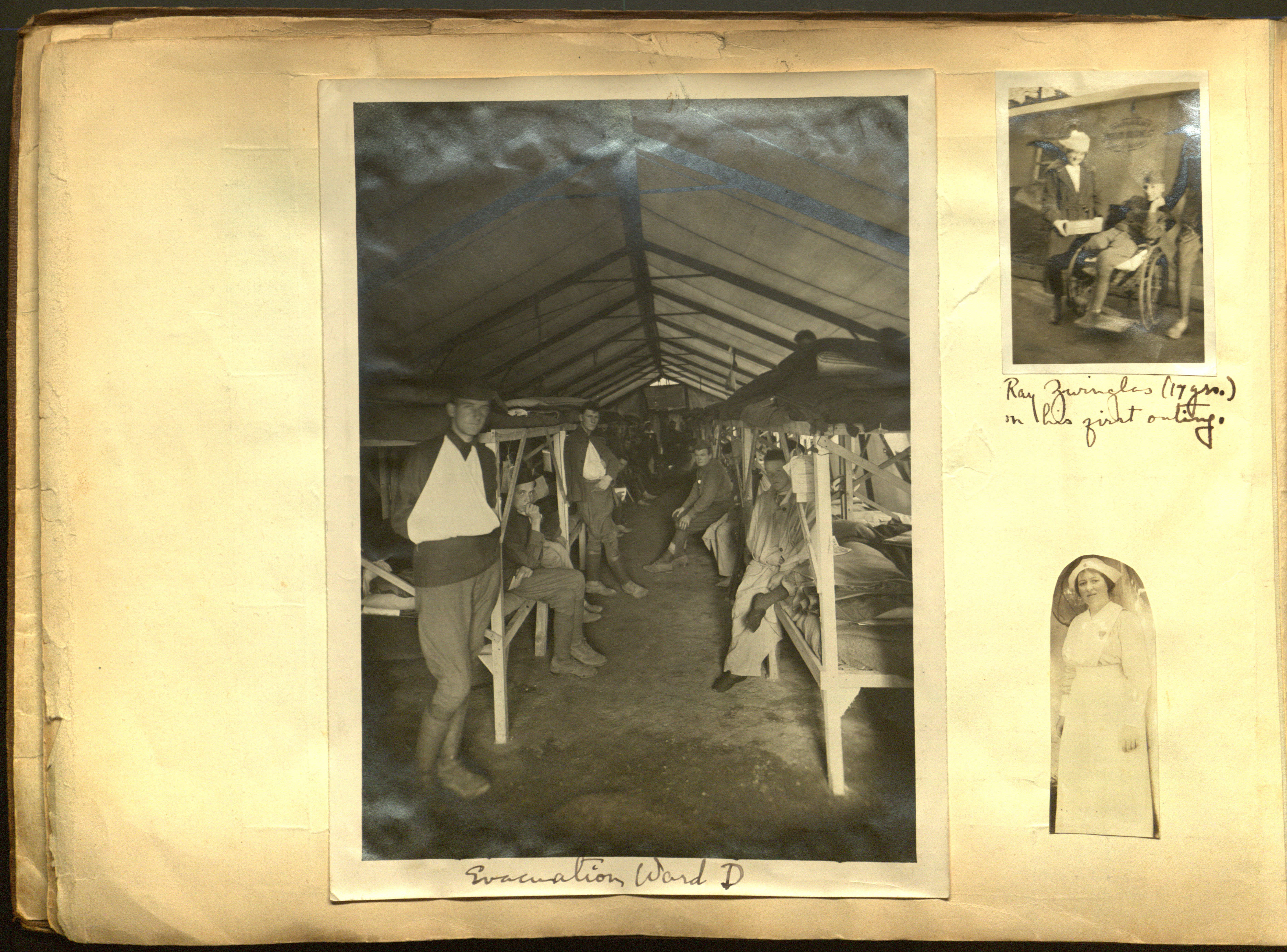

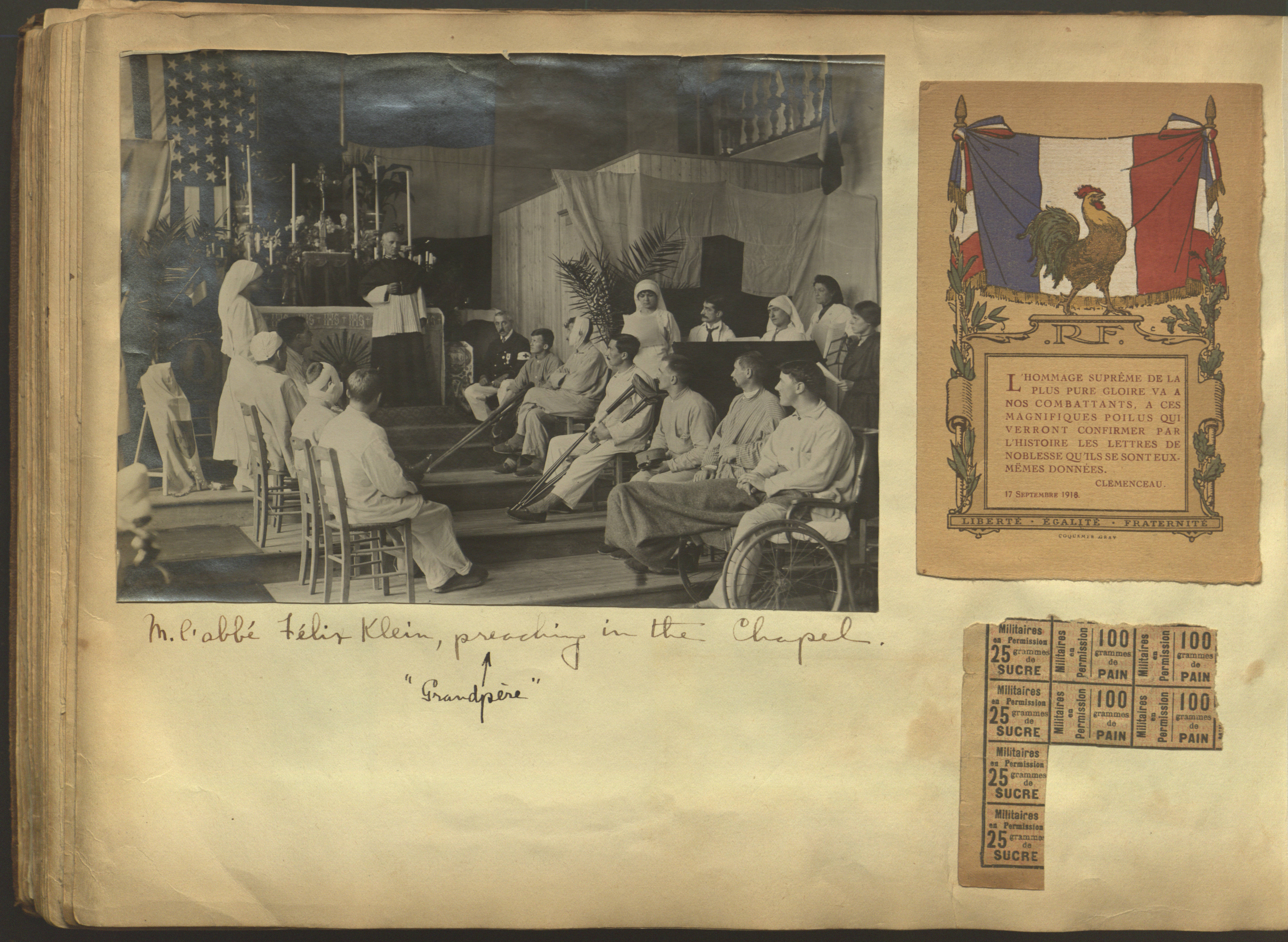

Others images also show nurses serving civilians, they became comforters of a context broken by the destruction of the war. Several posters depict female nurses standing aside of wounded soldiers, while others depict them taking actions holding men, performing medical assistance. There are, on the other hand, photographs of women in action, such as the images preserved in the Alma Clarke scrapbooks.

[virtual_slide_box id=”22″]

[virtual_slide_box id=”23″]

[virtual_slide_box id=”24″]

The relevance of the war propaganda is evidenced in Alma Clarke’s papers. In these, she used photographs along printed media to frame her experience and perception of the war. Alma and many other U.S. American women were part of the healers that aided in the physical and moral assistance of the soldiers in the battlefield.

[virtual_slide_box id=”33″]

[virtual_slide_box id=”25″]

While Alma captured her memories in a scrapbook, while other healers of the war, such as the British Vera Brittain, compiled her experience in a written memoire titled Testament of Youth. Vera Brittain was a student at Oxford when she decided to train as a nursing auxiliary. Her autobiography, Testament of Youth, records her experience before and during the Great War with profound sorrow by witnessing wounded and deceased soldiers during her time serving in England, Malta and France. Her fiancé Roland and her brother Edward died in combat.

Vera published her autobiography in 1933 and it became one of the most compelling stories about the effects of the war on the women and middle-class civilians in European youth population.

Muses: The War in the Domestic Space

“Knowing the women he loves is safe and waiting for his return becomes far more important to the soldier that the work provided by women as comrades in arms” –Susan Grayzel, Women’s Identities at War (1999).

Perhaps one of the most famous role of the women during the course of the Great War that has perpetuated until our days, is the women who stayed at home, waiting for her beloved one to return. Vera Brittain depicts part of this story, using her own voice to narrate her time in Oxford thinking about her brother and fiancé before deciding volunteering as nurse. This image of the lover, the mother, and the daughter in despair served to recruit soldiers. The messages embedded in the poster argues the necessity of men to involve in battler to defend their families and lovers, as well as for the safeguard of their male honor.

[virtual_slide_box id=”26″][virtual_slide_box id=”27″]

It is interesting to observe how these images affect the construction of men and women that lived in flesh and blood the consequences of the war in their social and family circles. Alma Clarke’s scrapbooks, for example, puts greater emphasis in the images of nurses and nuns as mothers and caretakers. Alma’s memories frame the way in she saw herself as a noncombatant in the battlefield, how the posters of recruitment from the Red Cross highlighted their role to “heal” the damages of the war.

However, Alma does not emphasize the domestic space in the same way as Frank Steed or the author, probably a man, of the Atlantic City scrapbook. The vision of these persons, which we can observe through the scrapbooks, reflect the gender and work relations in the midst of the war. These men, in Europe and in the U.S., compiled almost simultaneously media representing ideal versions of female as inspirational motifs of male heroism and in leisure environments.

[virtual_slide_box id=”28″][virtual_slide_box id=”29″]

The women portrayed by these men always look young, radiant, and smiling. These men, unlike Clarke who relied on her heroism as a nurse in the war, utilized photographs and printed media of real-life muses to create their memories. They focus on an image of female’s positive and embracing images to maintain the spirits high in the midst of a chaotic context.

[virtual_slide_box id=”31″][virtual_slide_box id=”32″]

But even though there were women who stayed at home, their duties went beyond the romanticized idea of the lady in despair. The propaganda that circulated in the country call the attention of the housewives to honor their men and serve their country by rationing food and donating supplies for the cause of the war. These media gives the idea women should serve a sort of penitence while men are overseas sacrificing their lives for them and for Columbia.

Providers: Working Women in the Homefront

While the image of Muses is very popular, the recruitment campaign during the war also aimed at involving women in different duties in the Homefront. The main goal of these tasks was to provide different means: food, weapons, information. Along with the role of nurses, this imagery of women turns empowering and provided a channel of social mobility in the public sphere of the U.S. In the absence of men, women took agency and went to the factories, to the fabrics, and to the farmland.

[virtual_slide_box id=”34″][virtual_slide_box id=”35″]

Then, women became providers, a fundamental system that secured the well-being of the soldiers and the stability of the country.

In terms of resources, the most prominent scope of propaganda targets the role of women working the land, planting the seed, and preserving food.

The image from the right exposes the sentiment that the battle was not isolated in Europe, but it affected the way people saw their quotidian task in the U.S. In this case, women became “the army land,” adjudicating implicit combatant roles that addressed their importance in the production of good for the civilian and military population. The image from the left, which belongs to the “Scrapbooks – the Home Front”, reasserts the role of women as providers, as the sources of the energy that would guarantee the success of the soldiers in battle. Furthermore, the images exposes the women also in a combatant role with her duty, since she is also wearing an uniform. Even though this image seems to be more patronizing than the previous, it does give an idea on how the domestic and the public sphere merged to create the female role of provider.

While the production and preservation of food appears as the most constant theme of the propaganda and printed media, there were also other two roles that increased female’s involvement in the war, as providers of weapons and providers of information.

[virtual_slide_box id=”36″][virtual_slide_box id=”37″]

These four dimensions of female imagery -Motherland, Healers, Muses, Providers- show the multifaceted character that surrounded women’s role in the early twentieth century. They also show the transitions of women from the domestic environment of the home, preserving food, to the public spheres working shoulder to shoulder, reaffirming an active position among men, occupying positions once limited in the past, and serving as examples for the nation. Women in the Great War played important roles that preserved the national sentiments in the home front and the battlefront, that healed the soldiers physically and spiritually. Most of all, these women opened new paths for the following generations, and in the same way as WWI transformed men, countries, and governments, it also changed and reaffirmed the importance of women at family, social, and economic levels.

Hopefully, this storytelling exposes how fundamental the presence of this imagined and real women was for the place female population occupies nowadays!

References/Further Reading

“An Auxiliary Nurse’s Scrapbook of the Great War.” Home Before the Leaves Fall. http://wwionline.org/articles/auxiliary-nurses-scrapbooks-great-war/

“Columbia (name).” Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_%28name%29#cite_note-3

Day, Elizabeth. “Testament of Youth: Vera Britain’s classic, 80 years on.” The Guardian, 2013. http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/mar/24/vera-brittain-testament-of-youth

“Enclosure: Poem by Phillis Wheatley, 26 October 1775.” Founders Online. National Archives. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0222-0002

Fox, Jo. “Women in World War One propaganda.” British Library. http://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/women-in-world-war-one-propaganda

Franke-Ruta, Garance. “When America was Female.” The Atlantic, 2013. http://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2013/03/when-america-was-female/273672/

Grayzel, Susan. Women’s Identities at War. Chapel Hill: UNC Press Books, 1999.

“Hail Columbia! with Lyrics; First American National Anthem – United States of America.” (Video.) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JPlQS1pzHdA

“I Wonder Who’s Kissing Her Now Sung By Billy Murray.” (Video.) Posted by WW1 Photos. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yI_-SrIvB-4

Kim, Tae H. “Where Women Worked During World War I.” Seattle General Strike Project. https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/kim.shtml#_ftn15

Marks, Ben. “Women and Children: The Secret Weapon of World War I Propaganda Posters.” Collectors Weekly, 2003. http://www.collectorsweekly.com/articles/women-and-children-the-secret-weapons-of-world-war-i-propaganda-posters/

“Military Nurses in World War I.” History and Collections. Women in Military Service for America Memorial Foundation, Inc. http://chnm.gmu.edu/courses/rr/s01/cw/students/leeann/historyandcollections/history/lrnmrewwinurses.html

Patch, Nathaniel. “The Story of Female Yeomen during the First World War.” National Archives 38 3 (2006). http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2006/fall/yeoman-f.html

Pitz, Marylynne. “Hail, Miss Columbia: Once a U.S. symbol she’s lost out to Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2008. http://www.post-gazette.com/ae/2008/03/18/Hail-Miss-Columbia-Once-a-U-S-symbol-she-s-lost-out-to-Uncle-Sam-Lady-Liberty/stories/200803180240

Prior, Neil. “How Land Girls helped feed Britain to victory in WW1.” BBC News, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-26238755

“Theres A Long Long Trail A Winding Sung By John McCormack.” (Video.) Posted by WW1 Photos. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DczcPkogrZU

“Vera Brittain. A Short Biography.” Learn Peace. http://www.ppu.org.uk/vera/

Welch, David. “Propaganda for patriotism and nationalism.” British Library. http://www.bl.uk/world-war-one/articles/patriotism-and-nationalism

“World War I and the American Red Cross.” American Red Cross. http://www.redcross.org/about-us/history/red-cross-american-history/WWII

“World War One: The many battles faced by WW1’s nurses.” BBC News, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-26838077

Pitz, Marylynne. “Hail, Miss Columbia: Once a U.S. symbol she’s lost out to Uncle Sam, Lady Liberty.” Pittsburgh Post-Gazette, 2008 http://www.post-gazette.com/ae/2008/03/18/Hail-Miss-Columbia-Once-a-U-S-symbol-she-s-lost-out-to-Uncle-Sam-Lady-Liberty/stories/200803180240

“Columbia (name). Wikipedia The Free Encyclopedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Columbia_%28name%29#cite_note-3”

Prior, Neil. “How Land Girls helped feed Britain to victory in WW1.” BBC News, 2014. http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-wales-26238755; Kim, Tae H. “Where Women Worked During World War I.” Seattle General Strike Project. https://depts.washington.edu/labhist/strike/kim.shtml#_ftn15

Patch, Nathaniel. “The Story of Female Yeomen during the First World War.” National Archives 38 3 (2006). http://www.archives.gov/publications/prologue/2006/fall/yeoman-f.html” target=”_blank; “World War I: 1914-1918.” Striking Women. http://www.striking-women.org/module/women-and-work/world-war-i-1914-1918

“Enclosure: Poem by Phillis Wheatley, 26 October 1775.” Founders Online. National Archives. http://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-02-02-0222-0002

Susan Grayzel, Women’s Identities at War: Gender, Motherhood, and Politics in Britain and France during the First World War (Chapel Hill, N.C.: University of North Carolina Press), p. 2.