Speculative fiction depicting society’s future has existed in popular format since the eighteenth century but did not truly gain mass popularity until the late nineteenth century. During this period, the powder keg of the Balkan states and rivalries between great powers like England and Germany sowed fear among Europeans. This fear resulted in the expansion of speculative fiction, and the creation of an entirely new sub-genre: the Imagined War sub-genre, which contemplated what a great war between the powers of Europe would be like. Writers of this genre predicted different aspects of World War I, sometimes with frightening accuracy. The existence of the Imagined War sub-genre shows that Europeans knew World War I would occur and that it was only a matter of time, and the fictional stories they wrote about what such a war would be like were a way to cope with that perceived inevitability. This is something society does to try to give people an idea about the future, as seen with modern science fiction portrayals of the future, ranging from the hopeful idealism of Star Trek to the stark bleakness of 1984. It was during the years leading up to World War I that this type of speculative fiction came into its own with Imagined War stories.

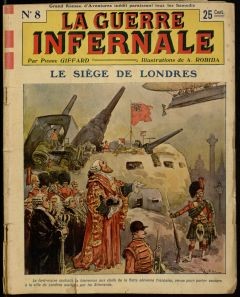

Imagined War stories commonly involved England and Germany as the main adversaries; however, they rarely considered the size and scale World War I ended up involving. This is likely due to the fact that World War I was the first war of its size and scale, and fiction writers of the period based their works on previous wars. These writers did often accurately predict the technological advancements and fallout of the conflict, though, possibly because of the rapid developments of the industrial revolution. Many of these involved invasions of England, such as William Le Queux’s 1906 serialization, The Invasion of 1910, or Germany, as seen in Karl Eisenhart’s 1900 book Die Abrechnung mit England (The Reckoning with England).

These stories typically enjoyed relative success among audiences, if not critical acclaim. This is curious as oftentimes they involved the defeat or invasion of the writer’s nation at the hands of a more powerful opponent. Stories of defeat, hopelessness in the face of the war machine, and the peril of the outbreak of war being as common as they were indicates the level of fear and worry present in Europe during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. These stories’ existence parallels the peril present in speculative fiction today – dystopias depicting the dangers of corrupt politics and the destruction of our environment reflect the fears of today’s society. The fears of European Society before World War I reflected in its speculative fiction involve the specter of foreign domination and a loss of native culture and values. European Imagined War writers could not conceive of the scale of the conflict or its capability to wipe out their way of live, but they were capable of fearing that possibility nonetheless. They expressed their fears of this in stories where their nations and cultures were stamped out by more advanced powers because their home nations lacked economic or military prowess, or loyal nationalism. This is in contrast to the Imagined War fiction of the United States of America, where Americans are never defeated. Even before The United States emerged as a true world power in the wake of World War II, Americans retained a sense of moral and national superiority. As such, American speculative war stories viewed the United States as a generator of peace, a hero, a technological power, whereas European stories felt much more dystopian and told more cautious tales of the dangers of the arms race. American stories were heavily patriotic because they depicted America as a great power, while European stories featured patriotism and nationalism in two ways: as a way to protect their own nation’s interest, or as a danger from other nations trying to impose their cultures upon the author’s native country.

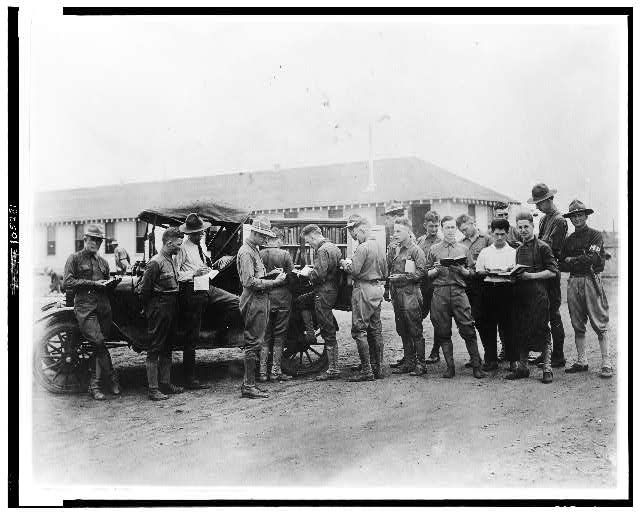

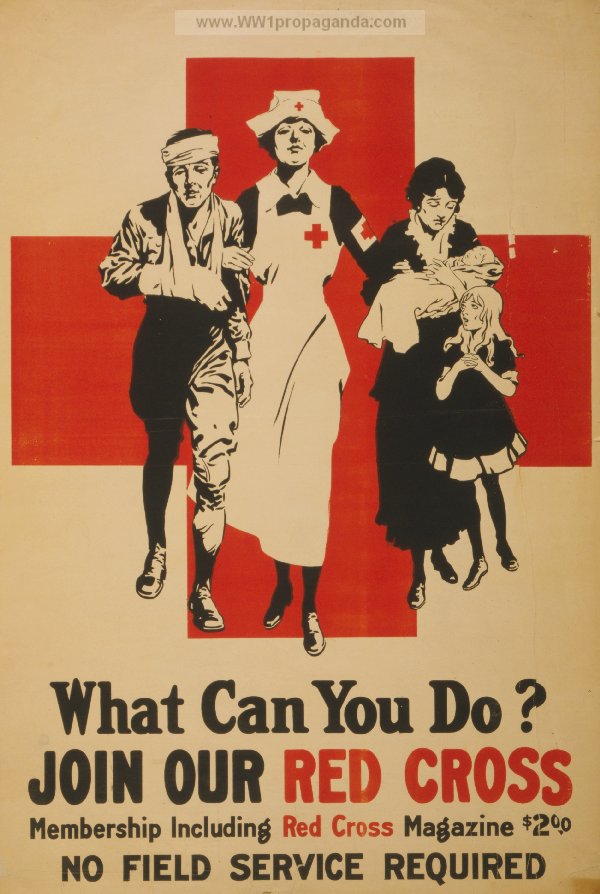

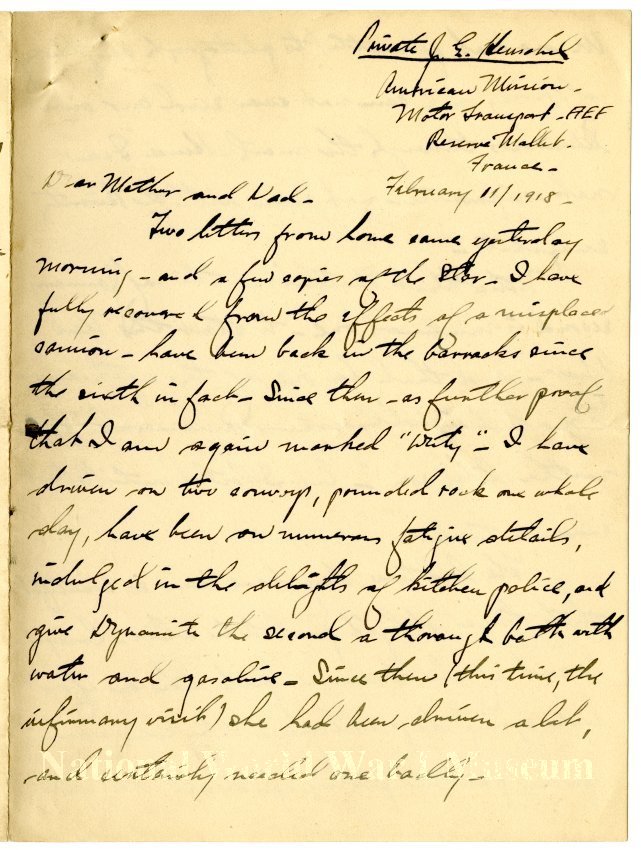

Also in contrast to American speculative war fiction is the focus placed most commonly on men – men as soldiers, workers, politicians, and bystanders. Women rarely entered the picture except as supporting characters. This is likely due to two connecting factors. First, the Imagined War sub-genre was a mainly European phenomenon leading up to World War I, and in Europe, women had not played many active parts in wartime yet. Women’s involvement in European war theaters would begin during World War I, as they took on the roles of nurses and industrial workers and couriers as men went off to fight. Until World War I occurred, women were not expected to involve themselves in war, and so even speculative fiction rarely involved them in such roles. A similar sub-genre had developed in the United States around the time of the American Civil War. However, due to Americans’ history with war and women’s involvement in conflicts as nurses, women featured more in American Imagined War fiction than did European women. The most prominent stories to feature American women were illicit romances – stories where lovers were forced to cross cultural divides between North and South in order to be together. If American fiction had featured Imagined War stories in the years preceding World War I, it is possible that stories about women such as Alma Clark, the American nurse who volunteered in French orphanages during World War I, and who kept a scrapbook of her travels, might have featured.

European Imagined War stories were stark cautionary tales of what a speculated Great War could do to the European continent and how nationalism and the arms race could decimate nations. Despite the fact that authors of stories in this sub-genre could not have imagined the scope of the eventual “war to end all wars,” the stories the wrote and their focus on nationalism and the arms race as both means of protection and dangers that caused the war predicted much of the war itself.

Bibliography and Works Cited:

“Alma A. Clarke Papers.” Alma A. Clarke Papers. Accessed November 7, 2015. http://triptych.brynmawr.edu/cdm/landingpage/collection/almaclarke

Katz, Demian. “Imagined Wars: Envisioning the War to Come.” Home Before the Leaves Fall: The Great War. Accessed November 7, 2015. https://wwionline.org/articles/imagined-wars/

Matarese, Susan M. American Foreign Policy and the Utopian Imagination. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2001.

Taylor, Amy Murrell. The Divided Family in Civil War America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

“Imagined Wars: Envisioning the War to Come.” WWI Online ::. Accessed November 7, 2015.

“Imagined Wars: Envisioning the War to Come.” WWI Online ::. Accessed November 7, 2015.

Matarese, Susan M. American Foreign Policy and the Utopian Imagination. Amherst: University of Massachusetts, 2001.

Taylor, Amy Murrell. The Divided Family in Civil War America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

“Alma A. Clarke Papers.” Alma A. Clarke Papers. Accessed November 7, 2015.