By Ann Shipley

She was brave. She was motherly yet girlish. She was sensitive and dutiful. She was adventurous yet maintained her femininity. She was a Red Cross Volunteer Nurse.

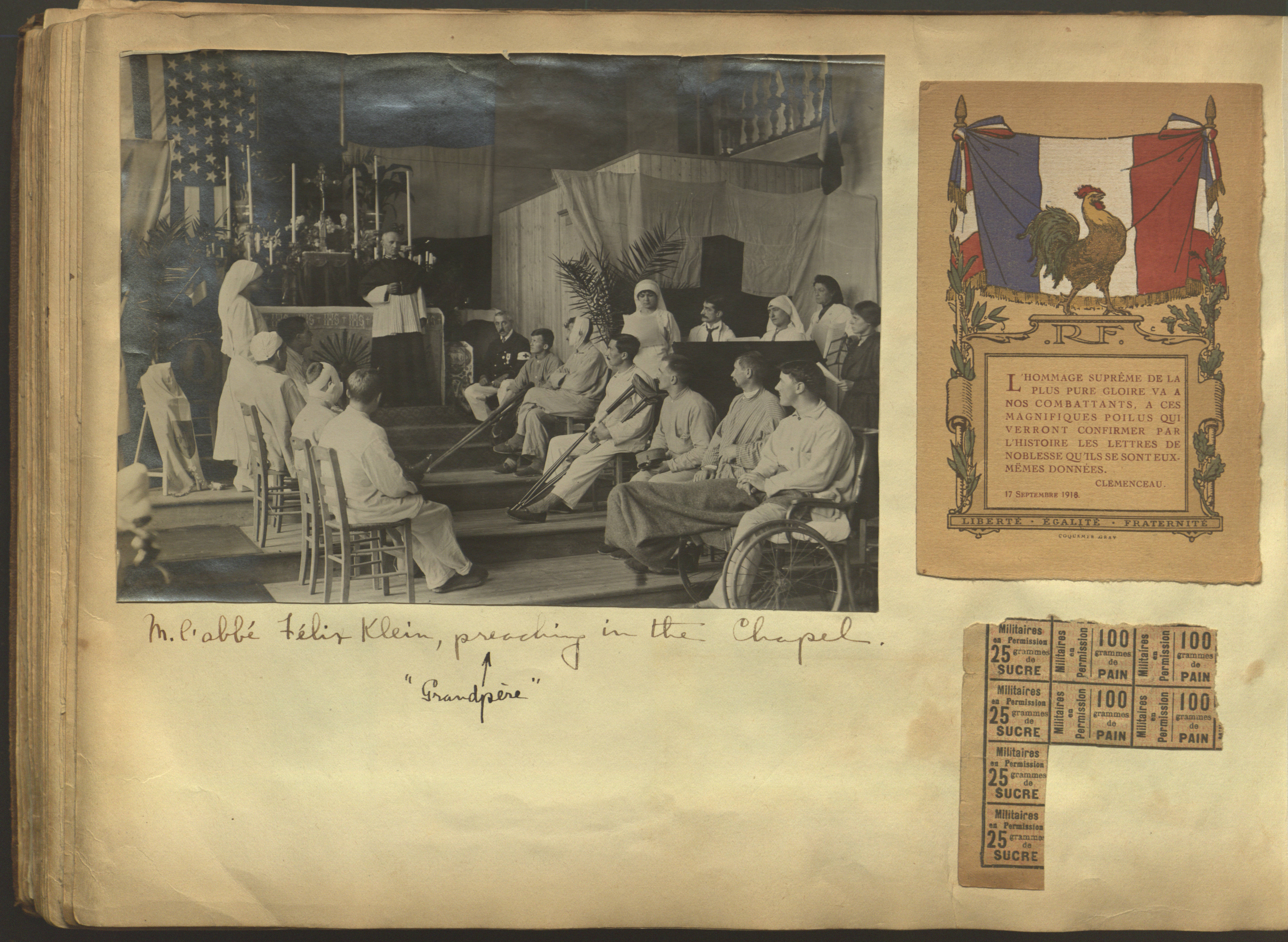

The American Red Cross (ARC) was largely untested as an organization on the eve of World War I. While the charitable group was founded several decades earlier in 1881, the massive scale and need of WWI challenged volunteers and their finances. An estimated one fifth of American households volunteered or were members of the ARC.[1] Many woman who traveled abroad, typically to France, wrote about their experiences in diaries, letters, and books. Some collected pictures, postcards, and mementos in scrapbooks. Comparing the two scrapbooks of Alma Clarke, a ARC Auxiliary Nurse stationed in France, to propaganda posters specifically from the Red Cross, one can begin to see similarities in how nurses positioned themselves to mimic vastly circulated Red Cross posters and vice versa. Clarke’s scrapbooks can be used to see the influences of propaganda and these can in turn be viewed as pieces of propaganda itself. Several pages even integrate propaganda posters alongside photographs as if to say they were the same thing. Clarke tailored her experience and memories of her time in France into digestible and familiar images for herself and her audience, therefore upholding the popular views and accepted experiences of the Great War.

[1] Lettie Gavin, American Women in World War I (Niwot: University of Colorado Press, 1997), 180.

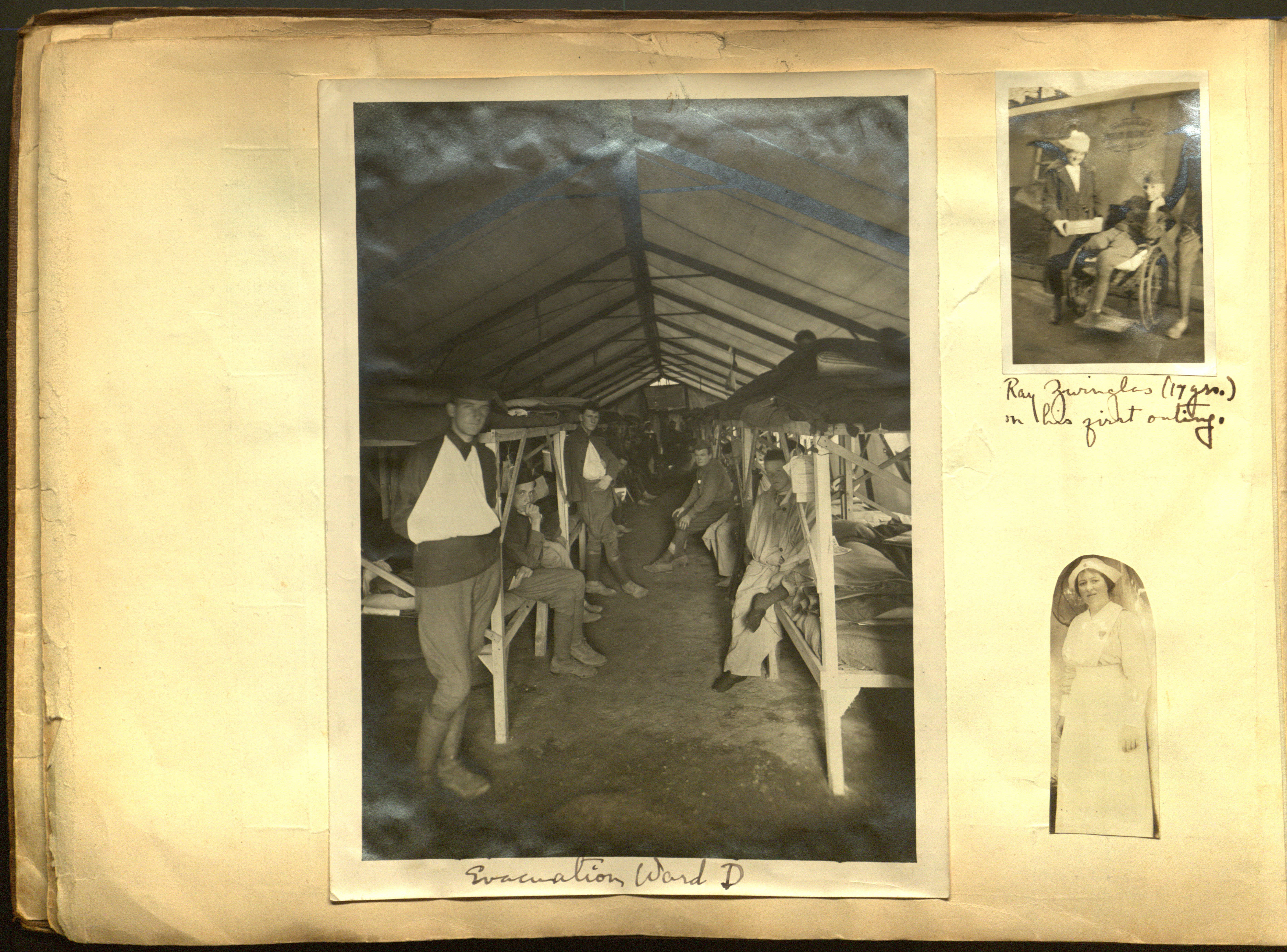

From her photographs and information available about Alma Clarke, her experience in France is representative of the average nurse. She includes pictures of where she worked, the wards for different groups, nurse class photos, and letters from home and patients in her scrapbooks. Choosing to analyze her scrapbooks and life allows us as historians to take a single case and see where wartime sentiments influence her choices and experience. Clarke’s work as an ARC nurse was critically important to the lives of many soldiers and now her work serves as a foundational point for wider views on the presentation of memories concerning World War I. When we compare her scrapbook to propaganda images circulated by the Red Cross found on ww1propaganda.com we begin to see parallels between the images collected by Clarke and these popular pictures. Going throughout this page, you will see sliders to compare these images side-by-side to illustrate how Clarke arranged her scrapbook to draw on popular themes and her work can be seen as a form of propaganda within itself.

Clarke’s inclusion of a print artfully featured at the beginning of her scrapbook already tells the reader that this book is not about the war but is about her humanitarian work. Here, the work of the nurses is presented as angelic and unassuming in their defense of life and mankind. Already Clarke’s scrapbooks follow a common pattern where nurses are not instructed to talk about and interact with the war, only the side effects and their work alongside the fighting.[2] The image of the nurse-heroine was an extremely popular trait and many nurses attempted to portray themselves as one, “even though they realized that it too distorted the reality of their professional contribution to the war.”[3] Clarke’s inclusion of images of nurses as “heroines of humanity” indicates that she saw her work in a similar light.

[2] Christine Hallett, Veiled Warriors: Allied Nurses of the First World War (New York: Oxford University Press, 2014), 3.

[3] Hallett, Veiled Warriors, 4.

Approaching propaganda is unique and can be analyzed in several different ways including using psychological, artistic, and historical methodologies. When we narrow down the scope to just Red Cross nursing images, several themes are commonly underlined. The courageous yet mistreated volunteer, the romantic nurse, and the nurse heroine are the main there kinds of nurses seen in prints and fiction.[4] Famous magazine illustrators and artists drew propaganda posters and Red Cross posters were often visually appealing.[5] The women depicted were familiar, naturally pretty, and could be anyone you knew. Posters were commissioned to recruit, raise funds, and change behaviors; they were meant to integrate themselves into all aspects of American life.[6]

[4] Hallett, Veiled Warriors, 2.

[5] Celia Kingsbury, For Home and Country: World War I Propaganda on the Home Front (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010), 8.

[6] Kingsbury, For Home and Country, 8.

Women were both targets and subjects of these posters but their work was centrally focused around morality.[7] The housewife was meant to protect and support her family and husband—who should be out fighting because she made it possible for him to do so. Propaganda made it so that women could be supporting the men in her life by supporting her country.[8] While the war and nursing allowed women more opportunities within the public sphere, she never left her domestic role as caregiver and supporter. Throughout Clarke’s scrapbooks, we see images of the domestically focused nurse.

[7] Kingsbury, For Home and Country, 10.

[8] Kingsbury, For Home and Country, 65.

Stories were also a major aspect of propaganda. Again, popular patterns of nurses as “Angels of the Battlefield” continue to position women as supporters of men and country instead of part of the fighting. War was not meant to turn women into men, quite the contrary. Nursing uniforms were meant to be neat and attractive to maintain the femininity of volunteers.[9] The ARC uniforms of pure white with a smart cap were noted for being “pretty.”[10] Women were involved in the war effort but they weren’t to become masculine; “if women die in their roles as nurses, ambulance drivers, or canteen workers, they must do so in a well-cut blouse.”[11] We can see the effects of the desire to remain pretty in Clarke’s scrapbooks as nurses appear neat and attractive while on duty. Snapshots and group photographs capture the feminine but modest uniform these women wore with pride. Their tidy and put together appearance helps to wash over any trauma they may have witnessed and gives the viewer an appearance of a world where harmony is achieved.

[9] Kingsbury, For Home and Country, 104-5.

[10] Kingsbury, For Home and Country, 104.

[11] Kingsbury, For Home and Country, 103.

One has to remember that propaganda is never neutral; its point is to make individuals do or change something in their lives for a certain purpose. The Red Cross was and is a technically neutral organization. However, the American Red Cross ceased their neutrality when the United States entered the war. Wilson formed a special arm of the war council to take over and efficiently run the ARC. Positions that women previously held on the board of the organization were “relegated to an advisory committee” to make room for an all male board.[12] Women across the ARC struggled to gain professional recognition for their nursing, yet there is no record of dissent from female officials on their removal from leadership positions. Many likely felt upset at being brushed aside, but causing problems was not part of Red Cross role; they were meant to fix things with a smile.

The most common “kind” of nurse we see in Clarke’s scrapbooks is the nurse heroine. This is a woman who selflessly serves and fulfills her duty to humanity and her country with a face of compassion. It is understandable why anyone would be drawn to emulate this character; she is the embodiment of goodness. Both professional and volunteer nursing presented an opportunity for women to “prove their worth—to have their work recognized and their professionalism valued.”[13] The women shown in Clarke’s photographs and mementos certainly present themselves as professionals and a necessity for the war effort. Nurses fought for the lives of their patients and the safe environments that were necessary for care.[14] We see the clean rooms and comfort of patients throughout Clarke’s scrapbooks, indicating to the viewer that she took pride in her fight for the soldier’s survival.

[12] Gavin, American Women in World War I, 181.

[13] Hallett, Veiled Warriors, 255.

[14] Christine Hallett, Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War (New York: Manchester University Press, 2009), 119.

There are an alarming number of similarities between Clarke’s creation of her scrapbooks and the creation of this digital project. One can imagine Clarke just copying and pasting pictures in her book as they developed and arranging pictures aesthetically, not even thinking about how the overall page and book will be interpreted. It is easy to just pick photographs at random and put them together because they look nice together. However, when dealing with propaganda posters and the personal scrapbooks of an ARC nurse, intention is necessary.

In this project, choosing the images had to be done with intention and decisions had to be firmly made. The images were chosen because of their similarities and because they spoke about Clarke’s presented experience in the war–what she though was important to preserve. Finding the slider tool to compare these images was essential and the tool from Juxtapose JS proved simple and easy to use. It helped to perfectly illustrate the parallels between national propaganda sentiments and an individual’s feelings towards what should be presented.

Clarke’s scrapbooks are a unique preservation of memory and one woman’s presentation of her wartime work. Placing it within its historical context showed the overlaps between nationally circulated images and the ones Clarke chose to preserve. Bringing this project to its digital form was a long experience as I was reminded that digital projects always—always—take longer than you think they will. I feel like the trainee nurses, ready to don my cap and white uniform, and feel that for a moment my individual contributions can be worth sometime.

Bibliography

Images

“English WWI Scrapbook.” Alma A. Clarke Papers. Accessed November 18, 2015. http://triptych.brynmawr.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/almaclarke/id/178

“French WWI Scrapbook.” Alma A. Clarke Papers. Accessed November 18, 2015. http://triptych.brynmawr.edu/cdm/compoundobject/collection/almaclarke/id/450

Red Cross Posters from: www.ww1propaganda.com

Secondary Sources

“World War I and the American Red Cross.” American Red Cross. Accessed November 18, 2015. http://www.redcross.org/about-us/history/red-cross-american-history/WWI.

Gavin, Lettie. American Women in the World War. Niwot: University of Colorado Press, 1997.

Hallett, Christine E. Containing Trauma: Nursing Work in the First World War. New York: Manchester University Press, 2009.

Hallett, Christine E. Veiled Warriors: Allied Nurses of the First World War. New York: Oxford University Press, 2014.

Kingsbury, Celia Malone. For Home and Country: World War I Propaganda on the Home Front. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2010.

Todd, Lisa M. “The Hun and the Home: Gender, Sexuality and Propaganda in First World War Europe.” In World War I and Propaganda, edited by Troy R.E. Paddock, 137-154. Boston: Brill Publishers, 2014.